Two young men, rich, charismatic, famous, both descendants of a king, locked in an acrimonious and very public conflict.

The odds ought to favour the elder of the two. He’s first in line to the throne and has the support of the entire royal family.

But things aren’t working out like that. It’s the younger man who’s driving the agenda. Officially, his name is Henry, though everyone calls him Harry. He has no palaces, courtiers, or regimental offices. He doesn’t even live in this country. But he has one advantage. He’s a natural at attracting attention.

The stage is set for a royal showdown. But this is one episode of The Crown you won’t see on Netflix. That’s because it took place over five hundred years ago in a field in Bosworth, Leicestershire.

The attention economy

Alright, comparing princes William and Harry to their medieval forbears Richard III and Henry VII is stretching it. This isn’t 1485: no one’s going to end up under a car park.

And yet, in the unfolding drama between William and Harry, it’s hard to avoid drawing historical parallels, no matter how tenuous they might be. The fact is, the unfolding tensions between the two royal brothers is a story both very old and very new.

Old, princes have always competed for power. Historically, this power was commodified in the form of land, estates, and royal regalia. For the Plantagenets and Tudors, power was tangible and three-dimensional, something you could drop on your foot.

New, because as the House of Windsor is discovering, power today is becoming increasingly intangible. To wield it, you don’t need castles, coronets, or even a claim to Calais.

What you need is the power to attract attention.

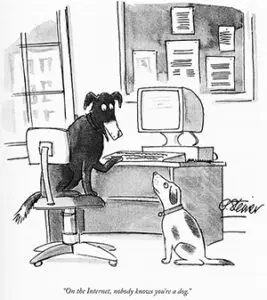

Whoever controls your eyes, controls the world

Attention is the most valuable commodity in the 21st century. Without it, governments and organisations are powerless. Attention shapes national policies, creates (and destroys) businesses, stabilises (and destabilises) markets, drives consumer trends, and for the winners, offers almost infinite wealth and influence. And all you need is an internet connection.

Losing attention

The reason why attention is so valuable is because of its scarcity. You and I have only so much of it – which may explain why you’re struggling to finish this article. But go easy on yourself: we’re programmed to be distracted – it’s one of our species’ defining attributes and one that we share with our nearest relatives, chimpanzees.

Being easily distracted explains why aeons ago we were so good at giving predators the slip. The problem comes when you transport this characteristic to the world of work. A 10,000-year-old early-warning system designed to help spot sabre-toothed tigers is the last thing you want when trying to finish a report or prepare a PowerPoint presentation.

More than anything, it explains why we’re powerless to resist smart phones.

According to research by Kings College, adults “hugely underestimate” how often they check their phones, with most adults thinking they checked them on average 25 times a day. The reality is closer to 80 times. Remarkably, almost half of those surveyed claimed “despite their best efforts” they were unable to stop themselves checking their phones, even when they knew they should be concentrating on other things. Presumably things like driving and crossing roads.

The challenge of paying attention is particularly acute for students. One study has found that students switch attention from one task to another every 65 seconds, while the median amount of time spent focusing on any one thing was just 19 seconds.

Paradoxically, the more distracted we are, the more we find distractions distracting. Studies show that office workers get distracted every 3 minutes. It then takes 23 minutes for them to get back to pre-distraction levels of concentration. No wonder so many people get to the end of the week without feeling they’ve achieved anything.

Attracting global audiences

As growing numbers of actors, singers, social media “influencers” have worked out, power, fame and wealth are no longer solely dependent on skills and talents, but on the ability to harness attention. Why else would an ex-Secretary of State appear on a TV reality show?

And because the internet makes attention infinitely scalable, those whose capacity for attention would once have been limited by the number of people they could physically reach, now have the opportunity to position themselves before worldwide audiences.

Perhaps this explains Harry and Meghan’s decision to go on TV. Twelve million people watched their Oprah interview and viewers recently spent 81 million hours watching the first three episodes of their Netflix series.

The risk of losing attention

Even for the winners, competing in the attention economy comes with risk. For all but a few, success will be fleeting. The same algorithms that got them to the top work tirelessly to spot and promote new attention-worthy talent. In the 1940s, Hollywood film studios had a conveyor belt of a hundred or so stars who they could build up and destroy according to the whims of the movie-going public. Today’s attention economy offers a similar prospect, only this time the talent pool is global, the riches infinite and the shelf-like is measured in hours not years.

The winter of their discontent

Thanks to Shakespeare and a certain archaeological find by the University of Leicester, Richard III and Henry VII are still very much in the news. Both still attract attention – although even they would eventually be eclipsed by Henry’s son and his six wives.

In 500 years’, time, will people still be paying attention to today’s royal saga?