Not exactly the most memorable phrase, but it did the trick. With the sound of a wave crashing on to a pebbled beach, all at once, in perfect unison, three hundred and fifty students turned over their question papers and began the exam.

At which point my work was done. As the starter, my role was to get the exam underway – to fire the starting gun, as it were. After that our team of expert invigilators would take over, fetching and carrying extra writing paper, replacing faulty pens, dispensing paracetamol, and generally watching over proceedings with hawk-eyed levels of beadiness.

And as the bells in the clock tower chimed, all that remained for me to do was to tip-toe out of the hall. My big moment had passed. Now I knew what the man who starts the Grand National must feel like once he’s pulled the lever and the horses and jockeys have galloped over the horizon. All that preparation then it’s over.

Admittedly, things hadn’t shaped up exactly as I’d planned. In my mind, the plan was to kick things off with a few well-chosen words of wisdom – an inspirational quote or two designed to calm student nerves; a carefully-crafted bon mot from a respected business leader or much decorated sportsperson. But when the moment arrived, it seemed as if everyone I was about to reference was either recently dead or recently publicly shamed. Not the sort of thing you want to distract the undergraduate mind with seconds before an exam. So it was au revoir to the inspirational sayings of Lance Armstrong and on with the script.

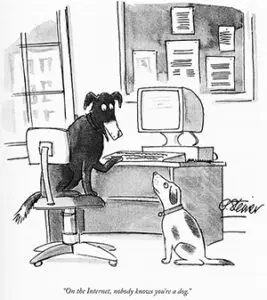

For as you and I know, exams are stressful enough without outside interference. These days, just gaining entry to the exam hall is like checking in for a long-haul flight. Upon arrival, students are required to divest themselves of all technological devices – phones, tablets, headphones, 3D glasses, jet packs. All gadgets must be placed in flight mode and stowed beneath seats. Fluids and prescription medicines must be carried in a transparent bag and declared to the invigilators. Wristwatches, until recently, were fine. All that changed with the invention of the smart watch. Smart watches are to exam invigilators what Magaluf is to the Spanish tourism industry. It won’t be long before someone orders a crackdown.

So there they were, three hundred-and fifty students ranked in rows, each with around fifteen hundred pounds’ worth of cutting-edge technology at his or her feet – more computing power per person than NASA used on the Space Shuttle. But rather than harnessing it and using it as a platform for learning, like most universities, we’re still getting to grips with how best to integrate it into mainstream education. This is why so many students are still required to sit two or three-hour exams. For many of them, this must feel outdated. Examinations made sense when ‘being educated’ meant being able to recall large amounts of information, but less so when that information is available everywhere via a multitude of devices.

That’s not to say that exams lack value. For some subjects, they remain an effective medium for assessing students’ levels of understanding. And what’s wrong with encouraging the development of memory skills? A good memory is also essential for mental wellbeing.

But exams should never be a default assessment tool – particularly given that the skills required to pass exams are rarely those required to function in the 21st Century.

In universities, the issue of authentic assessment is rapidly gaining traction. Authentic assessment is all about developing and applying types of assessment which from a student perspective are both meaningful and worthwhile. Authentic assessment includes presentations, team work tasks, work-based assignments and report-writing. And where some exams proscribe the use of technology, authentic assessment actually encourages students to integrate it into their learning.

A few years ago while invigilating another exam, a student asked if he could use his laptop. When I told him this wasn’t allowed, he asked why then had he been allocated a specially designed ‘laptop desk?’ When I told him that no such thing existed, he pointed triumphantly to the hole in the top right-hand corner and said, “Well what’s that for then?”

For him, a digital native, this was clearly and self-evidently the hole through which a computer’s power cables are threaded.

Actually, it was for an ink well.

Dr Paul Redmond is director of Student Experience and Enhancement at the University of Liverpool.